My mother was 16 when she discovered she was pregnant with me and I was born two months after she turned 17. One of the gifts of my mother’s early indoctrination into motherhood was that I spent time with my grandmothers while they were still fairly young. My father’s mother was born in 1912, the same year the Titanic went down, she loved to say.

Grandma Enright let me play in the garden at her house, the garden surrounding her patio. The patio had red and white concrete blocks and lots of green woven lawn chairs where I would lie wrapped in a beach towel after finally exiting the pool, fingertips wrinkled and white. She let me drink coke and cooked bacon and soft bowled eggs and played Go Fish with me time after time. Grandma had dinner ready for my grandfather every night and worked in the kitchen while he watched football in the rec room. The rec room would be filled with a smokey haze and the drapes on the sliding glass doors that led to the patio would be drawn to limit the light.

Grandma and Grandpa with Hannah

My grandmother drank a martini every day around dinner time. Grandpa would sometimes yell to her ‘be quiet Ruth.’

I was a stay-at-home Mom after my daughters were born and I remember a visit from my grandmother when Hannah was in kindergarten and Julia a toddler at home. My husband at the time worked long hours and I was the one in charge of cleaning, bed times, baths and food shopping. I was exhausted and rarely had time for myself, though I don’t think I would have known what to do with myself even if I had.

One morning after dropping Hannah off at school my Grandmother turned to me and said, eyeing me from head to toe, “don’t ever leave the house looking like that again. Women don’t wear sweatpants outside of the house. Get dressed.” I listened.

She also said, one night after we all ate dinner, “What are you going to make your husband for dinner?” He was working late, but I had the kid’s schedule to stick too. I told her he could just heat some leftovers up. Grandma clicked her tongue and said, “you better take care of your man, Robin or else he’ll stray.”

My mother’s mother, Grandma Schneider fascinated me. And bonus for my visits with her, my mother’s youngest sister was only a little over a year older than me. Beth was and remains my best friend, more sister than an aunt. We begged for sleepovers and more time together.

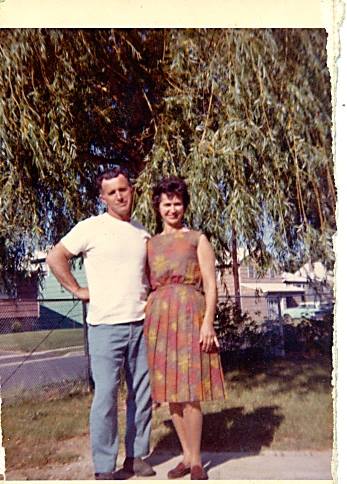

Grandma & Grandpa Schneider

Grandma Schneider would spend upwards of an hour in the morning with her makeup mirror at the kitchen table. She would slather on cream then wipe it off with a moist washcloth before massaging another beauty product on her face. Her skin would glow and I envied her olive-toned complexion when I compared it to my pale white skin. She told me it was never too early to take care of my skin.

I should always be a lady, she said. Smiles were good, anger was not. Though this was the time of letter writing and note passing, Grandma admonished, “Never write something that you don’t want to be read by others.” Grandma cooked an enormous Thanksgiving dinner after patting ‘Tom Turkey’ on the butt and thanking him for giving his life for our meal.

We rarely spoke on the phone and she never visited me after I moved out from under my parent’s roof, but after Hannah was born, she called me out of the blue. I had a bad case of the baby blues, hormones gone to hell and all I could do was cry, terrified that I wasn’t a good mother and completely confused as to who I was. I’ll never forget her voice as I listened to her through the telephone receiver, twisting the cord as I always did when on the phone. She told me she had experienced postpartum depression and she understood. Grandma said, “this will pass, Robin, this will pass.” Grandma knew. She was the only one who understood.

My Grandmothers were larger than life and I had them for so long I took them for granted. They lived to see me married and with children. Grandma Enright was around when I got divorced at 47, though when we spoke, she often forgot, and I never corrected her.

Both were strong women, but I realize today that I don’t know very much about the things they were passionate about beyond their families. I don’t know if they ever loved anyone other than my grandfathers, or if they had dreams to live a different life, have a profession, live in Rome or Michigan. I don’t know if they were truly happy or if they yearned to be on their own. I don’t know much about what made them laugh or caused them to cry. When I was a little girl, they were always taking care of their families and their men, never standing in the spotlight themselves.

I had so much time with them, but when I was old enough to ask, I was preoccupied with my own life, lulled into thinking that they would always be there because they always had been.

When people ask me who my role models are, who I look to for how to live my life as an older woman, I mention women like Ruth Bader Ginsberg or Gloria Steinham, Joan Didion, Anne Lamott, Mary Oliver, because I want the guidance of strong women, women who will encourage me to be true, to use my voice, to stop apologizing for my voice and to be brave enough to be real.

And yet, though my Grandmothers lived lives that are night and day different from mine, I suspect they would both tell me to live my best life. They would likely not understand me, they would likely be uncomfortable with my use of the word ‘fuck’ or my openness about my own personal life, but something tells me that just because they lived in a time of gender lines, they would be proud of me for being who I am.

I wish I could sit across from them, hold their wrinkled and arthritic fingers inside mine and say thank you for showing me the way even though the shoes we wore traveled different roads. Thank you for your strength and your love. Thank you.